|

|

|

Edward Curtis Resources

|

|

Featuring Edward S. Curtis's work--a biography, chronology, and archives of his writings and photographs

|

|

Edward Curtis Image Gallery holdings: 550

|

"Kiho carrier" - Qahatika, by Edward S. Curtis from The North American Indian Volume 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The Selawik | The North American Indian - Volume 20 | Curtis, Edward | | American Indian |

|

|

|

| The Kobuk | The North American Indian - Volume 20 | Curtis, Edward | | American Indian |

|

|

|

| The Noatak | The North American Indian - Volume 20 | Curtis, Edward | | American Indian |

|

|

|

| The Kotzebue Eskimo | The North American Indian - Volume 20 | Curtis, Edward | | American Indian |

|

|

|

| Eskimo of Cape Prince of Wales | The North American Indian - Volume 20 | Curtis, Edward | | American Indian |

|

|

|

| Eskimo of Little Diomede Island | The North American Indian - Volume 20 | Curtis, Edward | | American Indian |

|

|

|

| Eskimo of King Island | The North American Indian - Volume 20 | Curtis, Edward | | American Indian |

|

|

|

| Eskimo of Hooper Bay | The North American Indian - Volume 20 | Curtis, Edward | | American Indian |

|

|

|

| The Nunivak | The North American Indian - Volume 20 | Curtis, Edward | | American Indian |

|

|

|

| The Alaskan Eskimo: Introduction | The North American Indian - Volume 20 | Curtis, Edward | | American Indian |

|

|

|

|

|

Born in 1868 near Whitewater, Wisconsin, Edward Sheriff Curtis became one of America’s finest photographers and ethnologists. When the Curtis family moved to Port Orchard, Washington in 1887, Edward’s gift for photography led him to an investigation of the Indians living on the Seattle waterfront. His portrait of Chief Seattle’s daughter, Princess Angeline, won Curtis the highest award in a photographic contest.

Born in 1868 near Whitewater, Wisconsin, Edward Sheriff Curtis became one of America’s finest photographers and ethnologists. When the Curtis family moved to Port Orchard, Washington in 1887, Edward’s gift for photography led him to an investigation of the Indians living on the Seattle waterfront. His portrait of Chief Seattle’s daughter, Princess Angeline, won Curtis the highest award in a photographic contest.

Curtis opened his own business in 1897 with growing reputation as commercial photographer of romantic portraits, Indian subjects, and landscapes. His studies is called Edward S. Curtis, Photographer and Photoengraver.

In 1898, whilst hiking on Mount Rainier, Curtis discovered a group of lost scientists and leads them to safety. Amongst the group is George Bird Grinnell, a famed anthropologist and historian of the Cheyenne Indians. Curtis and Grinnell would become fast friends.

In 1904, Curtis' growing fame as a photographer lead to his invitation to photograph President Theodore Roosevelt’s children. President Roosevelt would subsequently become a major supporter of Curtis' work.

Inspired by Grinnell, and supported by J.Pierpoint Morgan, Edward S. Curtis devoted 30 years of photographing and documenting over eighty tribes west of the Mississippi, from the Mexican border to northern Alaska. During his time amongst the Crow Indians, they honored him with the name Auk-ba-axua Balat Duchay, “One Body Image Taker”. Upon its completion in 1930, Curtis’ opus, entitled The North American Indian, consisted of 20 volumes, each containing 75 hand-pressed photogravures and 300 pages of text. Each volume was accompanied by a corresponding portfolio containing at least 36 photogravures.

For more information about the life and work of Edward S. Curtis, see our chronology of Curtis' life below.

|

|

For basic background on Curtis' The North American Indian, read the biographical section above. The comments below refer to this monumental work.

FOREWORD

by President Theodore Roosevelt

to Curtis' multi-volume work The North American Indian

In Mr. Curtis we have both an artist and a trained observer, whose pictures are pictures, not merely photographs; whose work has far more than mere accuracy, because it is truthful. All serious students are to be congratulated because he is putting his work in permanent form; for our generation offers the last chance for doing what Mr. Curtis has done. The Indian as he has hitherto been is on the point of passing away. His life has been lived under conditions thru which our own race past so many ages ago that not a vestige of their memory remains. It would be a veritable calamity if a vivid and truthful record of these conditions were not kept. No one man alone could preserve such a record in complete form. Others have worked in the past, and are working in the present, to preserve parts of the record; but Mr. Curtis, because of the singular combination of qualities with which he has been blest, and because of his extraordinary success in making and using his opportunities, has been able to do what no other man ever has done; what, as far as we can see, no other man could do. He is an artist who works out of doors and not in the closet. He is a close observer, whose qualities of mind and body fit him to make his observations out in the field, surrounded by the wild life be commemorates. He has lived on intimate terms with many different tribes of the mountains and the plains. He knows them as they hunt, as they travel, as they go about their various avocations on the March and in the camp. He knows their medicine men and sorcerers, their chiefs and warriors, their young men and maidens. He has not only seen their vigorous outward existence, but has caught glimpses, such as few white men ever catch, into that strange spiritual and mental life of theirs; from whose innermost recesses all white men are forever barred. Mr. Curtis in publishing this book is rendering a real and great service; a service not only to our own people, but to the world of scholarship everywhere.

Theodore Roosevelt, October 1st, 1906

Introduction to a Spanish-language edition*

of The North American Indian

In 1896 Edward S. Curtis began a project to photographically record what he thought was a vanishing race, the American Indians. He believed that his photographs, together with an accompanying text, would provide a definitive publication of information about all the Native American tribes. He also thought that this ambitious project could be completed in 10 years. After 10 years of work, however, he had only just begun his efforts, and he had already spent all of his own financial resources on the project. J. Pierpont Morgan became the patron that Curtis needed to finish his dream, which finally took a total of 34 years, culminating when the final volume of The North American Indian was published in 1930.

The more than 40,000 photographs he shot were almost all recorded on glass negatives, either 11 x 14 inches or 14 x 17 inches in size. It was only toward the end of his project that he used a 6 x 8 inch reflex camera. The almost overwhelming difficulty of the photographic project and the stunning visual images earned Curtis a reputation as a great photographer. There is a tendency to overlook the difficulty of the process and the valuable insights Curtis gained into the Native American way of life over decades of living with them. He took great efforts to reach the inner meanings of the Indian life. He wrote,

"The task has not been an easy one…it often required days and weeks of patient endeavor before my assistants and I succeeded in overcoming the deep-rooted superstition, conservatism, and secretiveness so characteristic of primitive people, who are ever loath to afford a glimpse of their inner life to those who are not of their own ...

Curtis gained the trust of our First Peoples by living with them and demonstrating his respect for their ancestral traditions. This allowed him to speak with many tribal leaders about their sacred traditions. The importance of his writings on the history and culture of the diverse tribes should not be completely overshadowed by the brilliance of his photographs. Edward S. Curtis furnished a written record of great importance for both scholars and the general public, and a photographic record unequalled in all history.

Curtis was wrong when he wrote about the "vanishing race" of the American Indians, but it is undeniable that the way of life that Curtis recorded almost 100 years ago has all but vanished. The North American Indian therefore stands as a lasting chronicle of important insights into a traditional way of life that was still clinging to its sacred center and still focused on living in harmony with Nature. While each of the twenty volumes of The North American Indian focuses on different people and cultures, each one volume is still infused with the same basic relationship of man to Nature and thus his Creator. Curtis takes great efforts to explain the underlying relationship of each tribe to the sacred:

It is thus near to Nature that much of the life of the Indian still is; hence its story, rather than being replete with statistics of commercial conquests, is a record of the Indian's relations with and his dependence on the phenomena of' the universe - the trees and shrubs, the sun and stars, the lightning and rain - for these to him are animate creatures. Even more than that, they are deified, therefore are revered and propitiated, since upon them man must depend for his well-being.

At the same time Curtis conveyed the urgency of the situation of the Native Americans, because Curtis knew that the traditional ways, based on the sacred, were in the process of vanishing:

The passing of every old man or woman means the passing of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rites possessed by no other; consequently the information that is to be gathered, for the benefit of future generations, respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost for all time.

Even more than his words, the Curtis photographs portray qualities that are almost impossible to find in today's world, both because of the settings and clothing that are now lost, but also in the character of the faces. Where can you find so many people who possess the inward strength and grandeur that can only be obtained through the life of a traditional civilization? Because of the great care that Curtis took to place his photographic subjects in traditional dress and circumstances, the results are all the more striking and stimulating. Curtis would first find the most appropriate setting, without modern influences such as fences or structures. He would then discuss the proposed idea with the person to be photographed and a mutual decision would result that would best represent the spirit of the tradition. The Indians would then wear their finest clothing to recreate the vision of past splendor. This process creates a window to view the primordial aspects of the Indian life before the contact with the white civilization.

Some today argue that these photographs present a romanticized vision of the pre-reservation period, but most will agree that these compositions, created in consultation with olden-day nomads, more accurately portray the reality of traditional Plains life than photographs of living conditions in the early reservation period. Joe Medicine Crow, the Crow tribal historian and the last traditional Crow chief, spoke about the arranged photographs taken by Edward S. Curtis, who photographed his famous grandfather, Chief Medicine Crow: “Today [Curtis] is best known for his beautiful photographs because they capture the spirit of the olden-days when the Indians roamed free…. The old-timers only saw the photographs many years later. Most of them did not remember Curtis because he only spoke through an interpreter, but they really enjoyed seeing the photographs.” 1

It should be added that modern day Indian leaders feel that many of the Curtis photographs are among the finest that were ever taken of the Indians. My own Indian father, Thomas Yellowtail, one the most beloved American Indian spiritual leaders of the last century, had several Curtis photographs in his home which serve as a reminder of the spiritual foundation of his ancestors. It is increasingly difficult in today's society to carry on the spiritual traditions of the "olden days", as Yellowtail calls them, now that the life in constant contact with virgin Nature has ended; but their spirit lives on.

Edward S. Curtis preserved a lost window into “The Indian world”, which Frithjof Schuon notes, “represents on this earth a value that is irreplaceable; it possesses something unique and enchanting. When one encounters it in its unspoilt forms, one is aware that it is something altogether different from chaotic savagery; that it is human greatness, and at the same time harbors within itself something mysterious and sacred, which it expresses with profound originality.” 2 As you read The North American Indian, may youcome to understand the profound truth of this insight.

Michael O. Fitzgerald

Bloomington, Indiana.

*Adapted from Fitzgerald’s “Introduction” to the twenty-volume Spanish-language edition of The North American Indian published by Olaneta, Los Beduinos De America: El Indio Norteamericano, 1993

Notes

2 “Travel Journal, 1959,” published in The Feathered Sun.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

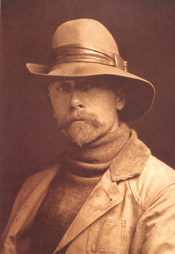

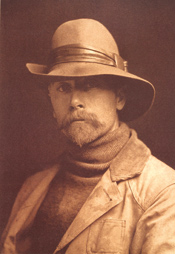

Edward Curtis in 1899

|

|

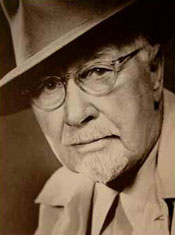

Edward Curtis in 1951

|

|

|

|

|

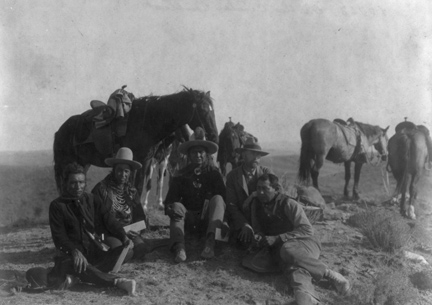

Curtis on Custer Outlook with his Crow Scouts - 1908

|

|

|

|

|

Curtis working in his camp

|

|

|

| 1868 |

Edward Sheriff Curtis born February 16, near Whitewater, Wisconsin. Edward’s father, Johnson Curtis, lost his health during the Civil War; cannot resume farming and becomes a minister. |

| 1874 |

Family moves to Cordova, Minnesota. |

| 1887 |

Family moves to Seattle, Washington. Builds cabin in Port Orchard, a ferry ride across Puget Sound. |

| 1888 |

Father dies of pneumonia in May. |

| 1891 |

Borrows $150 and goes into business with partner, Rasmus Rothi. Founds Rothi and Curtis, Photographers at 713 Third Avenue, Seattle. |

| 1892 |

Curtis at age 24 marries Clara Phillips. Rothi parts company with Curtis. Curtis forms new partnership with Thomas Guptill to form Curtis and Guptill, Photographers and Photoengravers at 614 Second Avenue, Seattle. |

| 1893 |

First child, Harold, born. |

| 1894 |

Guptill withdraws as partner. |

| 1895 |

Edward Curtis’ brother Asahel starts work as an engraver at the photo studio. |

| 1895–1896 |

Curtis photographs Princess Angeline, the daughter of Chief Sealth, from whom Seattle took its name. This could possibly be his first photograph. |

| 1896 |

Second child, Beth, born. Wins bronze medal from the Photographers’ Association of America for “excellency in posing, lighting, and tone.” |

| 1897 |

Enters business on his own with growing reputation as commercial photographer of romantic portraits, Indian subjects, and landscapes. Studio now called Edward S. Curtis, Photographer and Photoengraver. Gold discovered in the Canadian Yukon. Curtis sends his brother Asahel to Alaska to photograph the gold rush. |

| 1898 |

While hiking and photographing Mt. Rainier, Curtis discovers a group of lost scientists and leads them to safety. Two members of this group will change the course of Curtis’ life forever, Dr. C. Hart Merriam and Dr. George Bird Grinnell. Third child, Florence, born. |

| 1899 |

Accompanies E. H. Harriman expedition to Alaska as official photographer, by invitation of Grinnell and Merriam. It is on this expedition that Curtis learns how to approach photography in a scientific manner or method. Curtis wins first-place awards at the National Photographic Convention for three Indian images: Evening on the Sound, The Clamdigger,and The Mussel Gatherer. |

| 1900 |

Stays as guest with George Bird Grinnell on Crow Indian reservation in Montana; decides to devote himself full-time to photographing Indians. Makes first trip to the Southwest later that same year. |

| 1900–1906 |

Works as businessman and full-time photographer of Indians, photographing extensively among the tribes of the Southwest, Great Plains, and Pacific Northwest. Establishes basic elements of style and approach to photographing Indians. |

| 1904 |

Lewis and Clark Journal publishes first major feature about Curtis’ Indian work. Curtis envisions photographing all Indian tribes “who still retained to a considerable degree their primitive customs and traditions.” To achieve this goal, Curtis hires Adolph Muhr to manage his studio, thus freeing him to photograph. Curtis wins photo contest in Ladies’ Home Journal and is asked to photograph President Theodore Roosevelt’s children. Roosevelt becomes a major supporter of Curtis’ project. |

| 1905 |

Curtis, again through the help of his friends Merriam and Harriman, has a successful photographic show in Washington, D.C. |

| 1906 |

Convinces J. Pierpont Morgan to provide capital loan to begin publication of The North American Indian,a 20-volume, 20-portfolio work. |

| 1907 |

Publishes volume 1 of The North American Indian. |

| 1909 |

Fourth child, Katherine, born. |

| 1909 |

Runs into financial problems. J. P. Morgan advances Curtis an additional $60,000 and sets up The North American Indian, Inc., to oversee his investment. |

| 1910–1912 |

In further attempts to generate funds, Curtis creates a “picture-musical” production, complete with full orchestration of Indian music to accompany his slide lecture. |

| 1912 |

Forms the Continental Film Company as another attempt to create funds for The North American Indian. Produces a motion-picture documentation of the Kwakiutl people of British Columbia. |

| 1913 |

Publishes in volume 9 a memorial tribute to J. P. Morgan. Secures further support from Morgan’s son for The North American Indian. Moves Seattle studio to Fourth and University. Creates a new photographic process called Curt-tone, or Orotone, a positive photograph on glass. |

| 1914 |

Film In the Land of the Headhunters is completed. Although well received critically, the film does not bring in the much-needed funding for continued field research. |

| 1916 |

Curtis’ wife files for divorce, causing even further indebtedness. |

| 1916–1922 |

The North American Indian isput on hold. Curtis is not able physically or financially to continue his life project. |

| 1919 |

After divorce, Curtis moves to Los Angeles and establishes new studio in the famous Biltmore Hotel. With renewed spirit, Curtis enjoys new photo opportunities. |

| 1920–1936 |

Curtis starts working for the Hollywood studios, taking still photographs of scenes from such movies as DeMille’s The Ten Commandments. |

| 1922 |

Volume 12 of The North American Indian published. |

| 1922–1926 |

With the publication of volumes 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17, Curtis finishes his documentation of the Southwest Indians. |

| 1927 |

With help from daughter Beth, Curtis photographs the Indian people of Alaska. |

| 1930 |

Publishes volume 20 of The North American Indian. The project now complete, Curtis is physically and emotionally exhausted. |

| 1930–1948 |

Curtis never totally regains his health. However, he pursues an avid interest in mining and searching for gold. |

| 1935 |

The North American Indian, Inc., after having printed only 272-plus sets but selling just over 200, sells all assets to Charles Lauriat Books of Boston, Massachusetts. Lauriat will spend the next 40 years trying to sell sets of The North American Indian. |

| 1948 |

Begins correspondence with Harriet Leitch at the Seattle Public Library and writes for the first time since 1930 about the North American Indian. |

| 1952 |

On October 19, at the age of 84, Edward S. Curtis dies of a heart attack at the home of his daughter Beth in Whittier, California. |

This chronology of Edward S. Curtis' Life and Work appears in The Image Taker: The Selected Stories and Photographs of Edward S. Curtis edited by Gerald Hausman and Bob Kapoun. © World Wisdom, Inc 2009

|

|

|

|

The Image Taker: The Selected Stories and Photographs of Edward S. Curtis

Edited by Gerald Hausman and Bob Kapoun

Although Edward S. Curtis is well-known for his photography, the importance of his work as a historian and anthropologist is often overlooked. Capturing forever the myths and images of a vanishing way of life, the stories as well as the photographs of Edward S. Curtis offer the reader a bridge through time to the last generation of Indians from the “Buffalo Days.”

Selected from Curtis’ 20-volume masterwork, The North American Indian, this unique book The Image Taker features 181 photographs, rarely seen before in print, alongside the histories, myths, and legends of the 26 tribal nations portrayed.

This Book Features:

* A Foreword by Joe Medicine Crow, the last traditional Crow chief, who was a young boy when Curtis visited the Crow reservation and whose grandfather, Chief Medicine Crow, was photographed by Curtis.

* Traditional tribal stories and histories that Curtis recorded first hand, from the last generation of Indians to have lived in the pre-reservation “Buffalo Days”.

* While most volumes on Curtis feature images from his portfolio collections, The Image Taker features nearly 200 rarely-seen photographs from both The North American Indian text, and the unpublished collection held by the Library of Congress.

|

|

|

|

Indian Spirit: Revised and Enlarged

Gold Midwest Book Award for “Culture”

Gold Midwest Book Award for “Religion/Philosophy/Inspiration”

Used in college classes

Edited by Judith Fitzgerald and Michael Fitzgerald

Through its striking combination of stirring oratory and majestic portraiture from the Plains Indian pre-reservation “old-timers,” Indian Spirit reveals the very heart of the traditional Native American life-way: a world where dignity of soul, nobility of sentiments, discipline of gesture, and a sense of the Great Spirit in all things, reigned supreme. This heroic ideal of the Native American, blending the courage of the warrior with the wisdom of the priest, stands as a timeless exemplar for all peoples.

This fully revised and expanded new edition of Indian Spirit, the popular American Indian photograph-and-quote book, have been completely redesigned with many new pictures and motiffs, and features a new Foreword by Shoshone Sun Dance Chief James Trosper. (More)

|

|

|

|

|

Native Spirit: The Sun Dance Way

Gold Midwest Book Award for "Culture"

Silver Midwest Book Award for “Religion/Philosophy/Inspiration”

Silver Benjamin Franklin Award "New Age/Metaphysics/Spirituality"

Used in college classes

by Thomas Yellowtail, edited by Michael Fitzgerald

Native Spirit: The Sun Dance Way is the story of the remarkable preservation of an ancient cultural and spiritual way of life. In this companion book to the two documentary set Native Spirit & The Sun Dance Way, American Indian tribal elders and spiritual leaders tell of the struggle to preserve the way of their Grandfathers in the face of a government bent on their destruction. With over 100 color and sepia photographs from as early as 1903, along with the images from the only video footage officially sanctioned by the Sun Dance, this book reveals the symbolism and mystical beauty of the ancient Sun Dance ceremony, which still remains at the center of the spiritual life of many Plains Indians today.

Native Spirit: The Sun Dance Way includes rare interviews with such American Indian elders as John Arlee, Janine Pease, Joe Medicine Crow, James Trosper, Arvol Looking Horse, and Ines Talamantez. (More)

|

|

|

|

|

The Spirit of Indian Women

Gold Midwest Book Award for “Multicultural”

Gold Midwest Book Award for “Religion/Philosophy”

Used in college classes

Edited by Judith Fitzgerald and Michael Fitzgerald

What was the role of women in the world of nomadic American Indians in the 19th century? The Spirit of Indian Women provides a unique glimpse into a world that is almost inaccessible in our time. Through the combined power of photos, art, and the wisdom of traditional voices, modern readers can come to feel something of the timeless spirit of Indian women.

The Spirit of Indian Women also features an introduction by Janine Pease. (more)

|

|

|

|

|

The Cheyenne Indians: Their History and Lifeways, Edited and Illustrated

ForeWord Book of the Year Award Finalist for “History”

by George Bird Grinnell, edited by Joseph A. Fitzgerald

George Bird Grinnell (1849-1938) lived with and studied the last of the Cheyennes who had lived the nomadic life in the old West. He was the long-time editor of Field & Stream magazine and helped to establish both the Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks. During his career he documented several tribes of the old West, including this vivid account of the last of the Cheyenne Indians, who were forced to live out their lives as nomads. Grinnell recorded for posterity the former way of life of the Cheyennes, making his career, as the famed historian Stephen Ambrose has said, “of incalculable benefit to every student of Western or Indian history.”

The present book is an edited version of Grinnell’s great work on the Cheyenne, which Dee Brown, author of Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee has described as “a favorite source book for everyone interested in Plains Indians.” This edition is also fully illustrated and includes selections from three articles previously unpublished in book form.

(More)

|

|

Disclaimer:

The content of any third party sites which you link to from www.worldwisdom.com is entirely out of the control of World Wisdom, Inc. The inclusion of these links at www.worldwisdom.com does not imply that World Wisdom, Inc. has endorsed or is in any way associated with the information or materials offered or accessible at the third-party site.

Northwestern University's Digital Collection of The North American Indian offers a complete online record of Curtis' opus. Northwestern University's Digital Collection of The North American Indian offers a complete online record of Curtis' opus.

The Library of Congress holds an extensive collection of Curtis' work not published in The North American Indian The Library of Congress holds an extensive collection of Curtis' work not published in The North American Indian

Bob Kapoun, editor of The Image Taker offers fascinating information on Curtis' photographic techniques at his Rainbow Man Gallery website. Bob Kapoun, editor of The Image Taker offers fascinating information on Curtis' photographic techniques at his Rainbow Man Gallery website.

|

|

|

|

|

|