|

|

|

| OR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

René Guénon’s life and work

|

|

This site includes René Guénon’s biography, photos, online articles, slideshows, bibliography, links, and more.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

René Guénon (1886-1951) was a French metaphysician, writer, and editor who was largely responsible for laying the metaphysical groundwork for the Traditionalist or Perennialist school of thought in the early twentieth century. Guénon remains influential today for his writings on the intellectual and spiritual bankruptcy of the modern world, on symbolism, on spiritual esoterism and initiation, and on the universal truths that manifest themselves in various forms in the world’s religious traditions. His writings on Hinduism and Taoism are particularly illuminating in this latter regard.

René Guénon was born in Blois, France, in 1886. He grew up in a strict Catholic environment and was schooled by Jesuits. As a young man he moved to Paris to take up studies in mathematics at the College Rollin. However, his energies were soon diverted from academic studies and in 1905 he abandoned his formal higher education studies. Guénon submerged himself in certain currents of French occultism and became a leading member in several secret organizations such as theosophical, spiritualistic, masonic, and “gnostic” societies. In June, 1909 Guénon founded the occultist journal La Gnose. It lasted a little over two years and carried most of Guénon’s writings from this period.

Although Guénon was later to disown the philosophical and historical assumptions on which such occultist movements were built, and to contrast their “counterfeit spirituality” with what he came to see as genuine expressions of traditional esoterism, he always steadfastly opposed contemporary European civilization. There have been suggestions that during this period Guénon received either a Taoist or an Islamic initiation—or both. Whitall Perry has suggested that the “catalyzing element” was Guénon’s contact with representatives of the Advaita school of Vedanta.[1] It was during this period that he embarked on a serious study of the doctrines of Taoism, Hinduism, and perhaps Islam.

Guénon emerged now from the rather secretive and obscure world of the occultists and moved freely in an intensely Catholic milieu, leading a busy social and intellectual life. He was influenced by several prominent Catholic intellectuals of the day, among them Jacques Maritain, Fathers Peillaube and Sertillanges, and one M. Milhaud, who conducted classes at the Sorbonne on the philosophy of science. The years 1912 to 1930 are the most public of Guénon’s life. He attended lectures at the Sorbonne, wrote and published widely, gave at least one public lecture, and maintained many social and intellectual contacts. He published his first books in the 1920s and soon became well-known for his work on philosophical and metaphysical subjects.

Whatever Guénon’s personal commitments may have been during this period, his thought had clearly undergone a major shift away from occultism and toward an interest in esoteric sapiential traditions within the framework of the great religions. One central point of interest for Guénon was the possibility of a Christian esoterism within the Catholic tradition. (He always remained somewhat uninformed on the esoteric dimensions within Eastern Orthodoxy).[2] Guénon envisaged, in some of his work from this period, a regenerated Catholicism, enriched and invigorated by a recovery of its esoteric traditions, and “repaired” through a prise de conscience. He contributed regularly to the Catholic journal Regnabit, the Sacre-Coeur review founded and edited by P. Anizan. These articles reveal the re-orientation of Guénon’s thinking in which “tradition” now becomes the controlling theme. Some of these periodical writings found their way into his later books.

The years 1927 to 1930 mark another transition in Guénon’s life, culminating in his move to Cairo in 1930 and his open commitment to Islam. A conflict between Anizan (whom Guénon supported) and the Archbishop of Reims, and adverse Catholic criticism of his book The King of the World (1927), compounded a growing disillusionment with the Church and hardened Guénon’s suspicion that it had surrendered to the “temporal and material”. In January 1928 Guénon’s wife died rather abruptly, and, following a series of fortuitous circumstances, Guénon left on a three-month visit to Cairo. He was to remain there until his death in 1951.

In Cairo Guénon was initiated into the Sufic order of Shadhilites and invested with the name Abdel Wahed Yahya. He married again and lived a modest and retiring existence. “Such was his anonymity that an admirer of his writings was dumbfounded to discover that the venerable next-door neighbor whom she had known for years as Sheikh Abdel Wahed Yahya was in reality René Guénon.”[3]

A good deal of Guénon’s energy in the 1930s was directed to a massive correspondence that he carried on with his readers in Europe, people often in search of some kind of initiation, or simply pressing inquiries about subjects dealt with in his books and articles. Most of Guénon’s published work after his move to Cairo appeared in Études Traditionnelles (until 1937 titled Le Voile d’Isis), a formerly theosophical journal that was transformed under Guénon’s influence into the principal European forum for traditionalist thought. It was only the war that provided Guénon enough respite from his correspondence to devote himself to the writing of some of his major works including, The Reign of Quantity (1945).

In his later years Guénon was much more preoccupied with questions concerning initiation into authentic esoteric traditions. He published at least twenty-five articles in Études Traditionnelles dealing with this subject, from many points of view. Although he had found his own resting-place within the fold of Islam, Guénon remained interested in the possibility of genuine initiatic channels surviving within Christianity. He also never entirely relinquished his interest in Freemasonry, and returned to this subject in some of his last writings. Only shortly before his death did he conclude that there was no effective hope of an esoteric regeneration within either masonry or Catholicism.

Guénon was a prolific writer. He published seventeen books during his lifetime, and at least eight posthumous collections and compilations have since appeared. The œuvre exhibits certain recurrent motifs and preoccupations and is, in a sense, all of a piece. Guénon’s understanding of tradition is the key to his work. As early as 1909 we find Guénon writing of “… the Primordial Tradition which, in reality, is the same everywhere, regardless of the different shapes it takes in order to be fit for every race and every historical period.”[4] As Gai Eaton has observed, Guénon “believes that there exists a Universal Tradition, revealed to humanity at the beginning of the present cycle of time, but partially lost…. [His] primary concern is less with the detailed forms of Tradition and the history of its decline than with its kernel, the pure and changeless knowledge which is still accessible to man through the channels provided by traditional doctrine.”[5]

Guénon’s work, from his earliest writings in 1909 onward, can be seen as an attempt to give a new expression and application to the timeless principles which inform all traditional doctrines. In his writings he ranges over a vast terrain—Vedanta, the Chinese tradition, Christianity, Sufism, folklore and mythology from all over the world, the secret traditions of gnosticism, alchemy, the Kabbalah, and so on, always intent on excavating their underlying principles and showing them to be formal manifestations of the one Primordial Tradition. Certain key themes run through all of his writings, and one meets again and again such notions as these: the concept of metaphysics as transcending all other doctrinal orders; the identification of metaphysics and the “formalization”, so to speak, of gnosis (or jñana if one prefers); the distinction between exoteric and esoteric domains; the hierarchic superiority and infallibility of intellective knowledge; the contrast of the modern Occident with the traditional Orient; the spiritual bankruptcy of modern European civilization; a cyclical view of time, based largely on the Hindu doctrine of cosmic cycles; and a contra-evolutionary view of history.

Guénon repeatedly turned to oriental teachings, believing that it was only in the East that various sapiential traditions remained more or less intact. It is important not to confuse this Eastward-looking stance with the kind of sentimental exotericism nowadays so much in vogue. As Coomaraswamy noted, “If Guénon wants the West to turn to Eastern metaphysics, it is not because they are Eastern but because this is metaphysics. If ‘Eastern’ metaphysics differed from a ‘Western’ metaphysics—one or the other would not be metaphysics.”[6]

By way of expediency we may divide Guénon’s writings into five categories, each corresponding roughly with a particular period in his life: pre-1912 articles in occultist periodicals; exposés of occultism, especially spiritualism and theosophy; expositions of Oriental metaphysics; treatments both of the European tradition and of initiation in general; and lastly, critiques of modern civilization. This classification may be somewhat arbitrary, but it does help situate some of the focal points in Guénon’s work.

Although his misgivings about many of the occultist groups were mounting during the 1909-1912 period, it was not until the publication of two of his earliest books that he launched a full-scale critique: Theosophy: History of a Pseudo-Religion (1921) and The Spiritist Fallacy (1923). As Mircea Eliade has noted: “The most erudite and devastating critique of all these so-called occult groups was presented not by a rationalist outside observer, but by an author from the inner circle, duly initiated into some of their secret orders and well acquainted with their occult doctrines; furthermore, that critique was directed, not from a skeptical or positivistic perspective, but from what he called ‘traditional esoterism’. This learned and intransigent critic was René Guénon.”[7]

Guénon’s interest in Eastern metaphysical traditions had been awakened around 1909, and some of his early articles in La Gnose were devoted to Vedantic metaphysics. His first book, Introduction to the Study of the Hindu Doctrines (1921), marked Guénon as a commentator of rare authority. It also served notice of Guénon’s formidable power as a critic of contemporary civilization. Of this book Seyyed Hossein Nasr has written, “It was like a sudden burst of lightning, an abrupt intrusion into the modern world of a body of knowledge and a perspective utterly alien to the prevalent climate and world view and completely opposed to all that characterizes the modern mentality.”[8]

However, Guénon’s axial work on Vedanta, Man and His Becoming According to the Vedanta, was published in 1925. Other significant works in the field of oriental traditions include Oriental Metaphysics, delivered as a lecture at the Sorbonne in 1925 but not published until 1939, The Great Triad, based on Taoist doctrine, and many articles on such subjects as Hindu mythology, Taoism and Confucianism, and doctrines concerning reincarnation. Interestingly, Guénon remained more or less incognizant of the Buddhist tradition for many years, regarding it as no more than a “heterodox development” within Hinduism, without integrity as a formal religious tradition. It was only through the influence of Marco Pallis, one of his translators, and Ananda Coomaraswamy, that Guénon decisively revised his attitude.

During the 1920s, when Guénon was moving in the coteries of French Catholicism, he turned his attention to some aspects of Europe’s spiritual heritage. As well as numerous articles on such subjects as the Druids, the Grail, Christian symbolism, and folkloric motifs, Guénon produced several major works in this field, including The Esoterism of Dante (1925), St. Bernard (1929), and The Symbolism of the Cross (1931). Another work, Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power (1929), was occasioned by certain contemporary controversies.

The quintessential Guénon is to be found in two works that tied together some of his central themes: The Crisis of the Modern World (1927), and his masterpiece, The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times (1945). The themes of these two books had been rehearsed in an earlier one, East and West (1924). The books mounted an increasingly elaborate and merciless attack on the foundations of the contemporary European world-view.

While Guénon’s influence remains minimal in the Western academic community at large, he is the seminal influence in the development of traditionalism. Along with Coomaraswamy and Schuon, he forms what one commentator has called “the great triumvirate” of the traditionalist school. Like other traditionalists, Guénon did not perceive his work as an exercise in creativity or personal “originality”, repeatedly emphasizing that in the metaphysical domain there is no room for “individualist considerations” of any kind. In a letter to a friend he wrote, “I have no other merit than to have expressed to the best of my ability some traditional ideas.”[9] When reminded of the people who had been profoundly influenced by his writings, he calmly replied “… such disposition becomes a homage rendered to the doctrine expressed by us in a way that is totally independent of any individualistic consideration.”[10]

Most traditionalists regard Guénon as the “providential interpreter of this age.”[11] It was his role to remind a forgetful world, “in a way that can be ignored but not refuted, of first principles, and to restore a lost sense of the Absolute.”[12]

Adapted from Harry Oldmeadow, Journeys East: 20th Century Western Encounters with

Eastern Religious Traditions (Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, 2005), pp. 184-194.

NOTES

[1] Whitall Perry, “The Revival of Interest in Tradition”, in R. Fernando (ed) The Unanimous Tradition (Colombo: Sri Lanka Institute of Traditional Studies, 1991), pp. 8-9.

[2] Guénon’s slightly lopsided view of Christianity has been discussed in P. L. Reynolds René Guénon: His Life and Work (unpublished) pp. 9ff. See also B. Kelly: “Notes on the Light of the Eastern Religions”, in S. H. Nasr and William Stoddart (eds.), Religion of the Heart (Washington, D.C.: Foundation for Traditional Studies, 1991), pp. 160-161.

[3] Whitall Perry, “Coomaraswamy: The Man, Myth, and History”, in Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 11, No. 3, 1977, p. 160.

[4] René Guénon, “La Demiurge”, La Gnose 1909.

[5] Gai Eaton, The Richest Vein (Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis et Universalis, 1995), pp. 188-189.

[6] A. K. Coomaraswamy, The Bugbear of Literacy (London: Perennial Books, 1979), pp. 72-73.

[7] Mircea Eliade, “The Occult and the Modern World”, in Occultism, Witchcraft and Cultural Fashions (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1976), p. 51.

[8] S.H. Nasr, Knowledge and the Sacred (New York: Crossroad, 1981), p. 101.

[9] Perry, “The Man and His Witness”, in S.D.R. Singam (ed.), Ananda Coomaraswamy: Remembering and Remembering Again and Again (Kuala Lumpur: privately published, 1974), p. 7.

[10] Marco Bastriocchi, “The Last Pillars of Wisdom”, in S.D.R. Singam (ed.), Ananda Coomaraswamy, p. 356.

[11] Frithjof Schuon, “René Guénon: Definitions”, quoted by M. Bastriocchi, “The Last Pillars of Wisdom”, p. 359.

[12] Perry, “Coomaraswamy: The Man, Myth, and History”, p. 163.

|

|

World Wisdom books by René Guénon:

René Guénon's work is also found in these World Wisdom books:

- “Sacred and Profane Science”, in Science and the Myth of Progress, edited by Mehrdad Zarandi, 2004.

- “A Material Civilization”, in The Betrayal of Tradition: Essays on the Spiritual Crisis of Modernity, edited by Harry Oldmeadow, 2005.

- “St. Bernard”, in Ye Shall Know the Truth: Christianity and the Perennial Philosophy, edited by Mateus Soares de Azevedo, 2005.

- “Initiation and the Crafts” and “The Arts and Their Traditional Conception”, in Every Man An Artist: Readings in the Traditional Philosophy of Art, edited by Brian Keeble, 2005.

- “The Symbolism of Theater”, in The Essential Sophia, edited by Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Katherine O’Brien, 2006.

- “Haqîqa and Sharîa in Islam” in Sufism: Love and Wisdom, edited by Jean-Louis Michon and Roger Gaetani, 2006.

- “Oriental Metaphysics” in Light From the East: Eastern Wisdom for the Modern West, edited by Harry Oldmeadow, 2007.

- “The Language of the Birds” in The Underlying Religion: An Introduction to the Perennial Philosophy, edited by Martin Lings and Clinton Minnaar, 2007.

|

|

|

|

|

| Kabbalah | The Essential René Guénon: Metaphysics, Tradition and the Crisis of Modernity | Guénon, René | | Comparative Religion, Esoterism, Judaism, Tradition |

|

|

|

| Essential Characteristics of Metaphysics | The Essential René Guénon: Metaphysics, Tradition and the Crisis of Modernity | Guénon, René | | Comparative Religion, Metaphysics, Perennial Philosophy |

|

|

|

| What is Meant by Tradition | The Essential René Guénon: Metaphysics, Tradition and the Crisis of Modernity | Guénon, René | | Comparative Religion, Modernism, Perennial Philosophy, Tradition |

|

|

|

| Oriental Metaphysics | Tomorrow, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Winter, 1964); also in the book "The Underlying Religion" | Guénon, René | | Comparative Religion, Metaphysics, Modernism, Perennial Philosophy, Spiritual Life, Tradition |

|

|

|

| Al-Faqr | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 7, No. 1. (Winter, 1973) | Guénon, René | | Comparative Religion, Esoterism, Metaphysics, Spiritual Life |

|

|

|

Guénon here undertakes to show how the Taoist tradition is an integral part, though mostly hidden, of the ancient Chinese tradition with its origin in pre-history. This earlier tradition, first visible to history in the I Ching, adapted itself to later conditions through the birth of two parallel and reciprocal doctrinal forms, Taoism and Confucianism. Guénon’s more general objective is to illustrate how “traditional doctrines…contain in themselves from the very beginning the possibilities of all conceivable developments…and also the possibilities of all the adaptations which might be required by later circumstances.” The author demonstrates how the particular application here, namely the Chinese tradition, from a common root was divided into a doctrine of “pure metaphysics” (Taoism) and “the practical domain [or]…the realm of social applications” (Confucianism). The last part of the essay considers how the “real influence of Taoism can be extremely important [in China], while always remaining hidden and invisible.”

| Taoism and Confucianism | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 6, No. 4. (Autumn, 1972) | Guénon, René | | Comparative Religion, Eastern Religion, Esoterism, History, Metaphysics, Mythology or Legend, Perennial Philosophy, Symbolism, Tradition |

|

|

|

In referring back to an earlier essay, "The Heart and the Cave," René Guénon explores the mutual relationship between the universal symbols of the mountain and the cave in various traditions. He suggests that the mountain ("the spiritual center" or "Absolute Reality") can also be represented by an upward-pointing triangle, and that the cave ("manifestation") can be represented by a downward-pointing triangle. He goes on to describe the many ways in which the two triangles (and thus the "mountain" and the "cave") can interact in geometric space. For example, the upward-pointing triangle can have the downward-pointing triangle contained within it, or outside and below it, and so on. These geometrical relationships recall, for Guénon, a multitude of relationships in sacred space that represent the meeting of divine realities and their earthly manifestations.

| The Mountain and the Cave | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 5, No. 2. ( Spring, 1971) | Guénon, René | | Comparative Religion, Esoterism, Metaphysics, Perennial Philosophy, Symbolism, Tradition |

|

|

|

| The Symbolism of Theatre | The Essential Sophia | Guénon, René | | Symbolism |

|

|

|

This excerpt from Guénon's book Man and His Becoming According to the Vedanta (1958 translation by Richard C. Nicholson) is an important piece in that it draws a very precise distinction between how the term "Self" is used in traditionalist/perennialist writings as well as in the metaphysics of Vedantic and other traditional doctrines, and its "misuse" by modern theosophists and others. This distinction is of the utmost importance in understanding many esoteric doctrines, as well as traditionalist metaphysics.

| Fundamental Distinction between the Self and the Ego | A page on sophia-perennis.com with some links to information on Guénon | Guénon, René | | Metaphysics |

|

|

|

This is an article on www.studiesincomparativereligion.com in which René Guénon examines correspondences in ancient Hindu, Celtic, and Greek traditions in which the symbols of the wild boar and the bear appear.

| The Wild Boar and the Bear | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 1, No. 1. ( Winter, 1967) | Guénon, René | | Symbolism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Guénon has rendered us an inestimable service in presenting and expounding the crucial ideas of metaphysical science and pure intellectuality, of integral tradition and traditional orthodoxy, of symbolism and esoterism; and then in defining and condemning, with implacable realism, the modern aberration in all its forms.”

—Frithjof Schuon, author of The Transcendent Unity of Religions

“No living writer in modern Europe is more significant than René Guénon, whose task it has been to expound the universal metaphysical tradition that has been the essential foundation of every past culture, and which represents the indispensable basis for any civilization deserving to be so-called.”

—Ananda Coomaraswamy, author of Hinduism and Buddhism

“Apart from his amazing flair for expounding pure metaphysical doctrine and his critical acuteness when dealing with the errors of the modern world, Guénon displayed a remarkable insight into things of a cosmological order. . . . He all along stressed the need, side by side with a theoretical grasp of any given doctrine, for its concrete—one can also say its ontological—realization failing which one cannot properly speak of knowledge.”

—Marco Pallis, author of A Buddhist Spectrum

“There are those whose vocation it is to provide the keys with which the treasury of wisdom of other traditions can be unlocked, revealing to those who are destined to receive this wisdom the essential unity and universality and at the same time the formal diversity of tradition and revelation.”

—Seyyed Hossein Nasr, University Professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University, and author of Islam : Religion, History, and Civilization and The Heart of Islam: Enduring Values for Humanity

“The Collected Works of René Guénon brings together the writings of one of the greatest prophets of our time, whose voice is even more important today than when he was alive.”

—Huston Smith, author of The World’s Religions and Why Religion Matters

“In a world increasingly rife with heresy and pseudo-religion, Guénon had to remind twentieth century man of the need for orthodoxy, which presupposes firstly a Divine Revelation and secondly a Tradition that has handed down with fidelity what Heaven has revealed. He thus restores to orthodoxy its true meaning, rectitude of opinion which compels the intelligent man not only to reject heresy but also to recognize the validity of faiths other than his own if they also are based on the same two principles, Revelation and Tradition.”

—Martin Lings, author of Ancient Beliefs and Modern Superstitions

“To a materialistic society enthralled with the phenomenal universe exclusively, Guénon, taking the Vedanta as point of departure, revealed a metaphysical and cosmological teaching both macrocosmic and microcosmic about the hierarchized degrees of being or states of existence, starting with the Absolute . . . and terminating with our sphere of gross manifestation.”

—Whitall N. Perry, author of A Treasury of Traditional Wisdom

“Many of Guenon’s books . . . are such potent and detailed metaphysical attacks on the downward drift of Western civilization as to make all other contemporary critiques seem half-hearted by comparison.”

—Jacob Needleman, editor of The Sword of Gnosis

“Guénon established the language of sacred metaphysics with a rigor, a breadth, and an intrinsic certainty such that he compels recognition as a standard of comparison for the twentieth century.”

—Jean Borella, author of Guénonian Esoterism and Christian Mystery

“René Guénon was the chief influence in the formation of my own intellectual outlook (quite apart from the question of Orthodox Christianity). . . . It was René Guénon who taught me to seek and love the truth above all else, and to be unsatisfied with anything else.”

—Fr. Seraphim Rose, author of Not of This World

“If during the last century or so there has been even some slight revival of awareness in the Western world of what is meant by metaphysics and metaphysical tradition, the credit for it must go above all to Guénon. At a time when the confusion into which modern Western thought had fallen was such that it threatened to obliterate the few remaining traces of genuine spiritual knowledge from the minds and hearts of his contemporaries, Guénon, virtually single-handed, took it upon himself to reaffirm the values and principles which, he recognized, constitute the only sound basis for the living of a human life with dignity and purpose or for the formation of a civilization worthy of the name.”

—Philip Sherrard, author of Christianity: Lineaments of a Sacred Tradition

|

|

|

|

| The Preface from The Essential René Guénon | The Essential René Guénon: Metaphysics, Tradition and the Crisis of Modernity | Herlihy, John | | Guénon, René |

|

|

|

Noted traditionalist author Marco Pallis responds to a previous issue's correspondence on reincarnation. He begins with an objective look at Guénon's tendency to use a harsh tone when attacking modern tendencies, but also charmingly notes this necessary mission requires "special qualities, in the man, such as rarely go with delicately adjusted expression." Pallis makes some very interesting points in his response to Mr. Calmeyer's correspondence, summarized in the phrase that "human birth is a rare and correspondingly precious opportunity." Pallis suggests several corrections to Guénon's conclusions on reincarnation, and offers some thought-provoking insights on the subject in general.

| Correspondence on reincarnation | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 1, No. 1. ( Winter, 1967) | Pallis, Marco | | Buddhism |

|

|

|

This is a transcript of a lecture given in the autumn of 1994 at the Prince of Wales Institute in London and sponsored by the Temenos Academy. Martin Lings was the secretary of Guénon for the last years of the latter's life, and here Lings gives a biographical sketch of Guénon that includes Lings' own unique perspective as a friend and an eminent traditionalist thinker.

| René Guénon | The online library of articles at religioperennis.org | Lings, Martin | | Comparative Religion |

|

|

|

|

3 entries

(Displaying results 1 - 3)

|

View : |

|

Jump to: |

|

Page:

[1]

of 1 pages

|

|

|

Loading... |

|

|

|

|

|

Books in French (Original Editions)

Introduction générale à l’Étude des doctrines hindoues. Paris: Éditions Trédaniel, 1921.

Le Théosophisme, histoire d’une pseudo-religion. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1921.

L’Erreur spirite. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1923.

Orient et Occident. Paris: Éditions Trédaniel, 1924.

L’Ésotérisme de Dante. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1925.

L’Homme et son devenir selon le Vedanta. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1925.

La crise du monde moderne. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1927.

Le Roi du Monde. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1927.

Autorité spirituelle et pouvoir temporel. Paris: Éditions Trédaniel, 1929.

Saint Bernard. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1929.

Le Symbolisme de la Croix. Paris: Éditions Trédaniel, 1931.

Les États multiples de l’Etre. Paris: Éditions Trédaniel, 1932.

La Métaphysique orientale. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1939.

Le Règne de la Quantité et les Signes des Temps. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1945.

La Grande Triade. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1946.

Les Principes du Calcul infinitésimal. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1946.

Aperçus sur l’Initiation. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1946.

Initiation et Réalisation spirituelle. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1952.

Aperçus sur l’ésotérisme chrétien. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1954.

Symboles de la Science sacrée. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1962.

Études sur la franc-maçonnerie et le compagnonnage, vol.1. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1964.

Études sur la franc-maçonnerie et le compagnonnage, vol.2. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1965.

Études sur l’Hindouisme. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1967.

Formes traditionnelles et cycles cosmiques. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1970.

Aperçus sur l’ésotérisme islamique et le taoïsme. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1973.

Mélanges. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1976.

Comptes rendus. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1986.

Articles et Comptes-Rendus. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 2002.

Écrits pour Regnabit. Paris: Arché, 1999.

Psychologie: Notes de cours de philosophie (1917-1918) attribuées à René Guénon. Paris: Arché, 2001.

Books in English (Collected Works of René Guénon Series)

Introduction to the Study of the Hindu Doctrines. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Theosophy, the History of a Pseudo-Religion. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

The Spiritist Fallacy. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

East and West. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

The Esoterism of Dante. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2005.

Man and His Becoming According to the Vedanta. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

The Crisis of the Modern World. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

The King of the World. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

The Symbolism of the Cross. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

The Multiple States of the Being. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

The Great Triad. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Metaphysical Principles of the Infinitesimal Calculus. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Perspectives on Initiation. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Initiation and Spiritual Realization. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Insights into Christian Esoterism [including Saint Bernard]. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Symbols of Sacred Science. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Studies in Freemasonry and the Compagnonnage. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2005.

Studies in Hinduism [including Oriental Metaphysics]. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Traditional Forms and Cosmic Cycles. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Insights into Islamic Esoterism and Taoism. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Miscellanea. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Books and Articles on the Author

Robin Waterfield, René Guénon and the Future of the West. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2002.

Frithjof Schuon, René Guénon: Some Observations. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004.

Paul Chacornac, The Simple Life of René Guénon. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2005.

Jean Borella, Guénonian Esoterism and Christian Mystery. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2005.

Graham Rooth, Prophet for a Dark Age: A Companion to the Works of René Guénon. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press, 2008.

Marco Pallis, “A Fateful Meeting of Minds: A.K. Coomaraswamy and R. Guénon”, in Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 12, Nos. 3, 4, 1978 and The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, edited by Rama P. Coomaraswamy. Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, 2004.

Martin Lings, “René Guénon”, in Sophia, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1995 and The Essential René Guénon: Metaphysics, Tradition, and the Crisis of the Modern World, edited by John Herlihy. Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, 2009.

James Crouch, “Biographical Sketch”, in René Guénon, East and West. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis et Universalis, 1995.

Harry Oldmeadow, “Biographical Sketch”, in René Guénon, The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis et Universalis, 1995.

Marco Pallis, “The Veil of the Temple: A Study of Christian Initiation”, Sophia, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1999.

Martin Lings, “Frithjof Schuon and René Guénon”, Sophia, Vol. 5, No. 2, 1999.

Marco Pallis, “Supplementary Notes on Christian Initiation”, Sophia, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2000.

Jean Borella, “René Guénon and the Crisis of the Modern World”, Sacred Web, Vol. 9, 2002.

Seyyed Hossein Nasr, “The Influence of René Guénon in the Islamic World”, Sophia, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2002.

William Kennedy, “René Guénon and Roman Catholicism”, Sophia, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2003.

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, “Eastern Wisdom and Western Knowledge”, in The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, edited by Rama P. Coomaraswamy. Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, 2004.

Wolfgang Smith, “Modern Science and Guénonian Critique”, Sophia, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2003-4.

Renaud Fabbri, “The Question of Posthumous Conditions according to Mulla Sadra and René Guénon”, Sophia, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2003-4.

Peter Samsel, “Mathematical Implications of the Metaphysics of René Guénon”, Sophia, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2006.

Peter Samsel, “Seeing with Two Eyes: René Guénon, Ananda Coomaraswamy, and the Complementary Reassertion of Traditional Metaphysics”, Sacred Web, Vol. 18, 2006.

Whitall. N. Perry, “The Revival of Interest in Tradition”, in The Underlying Religion: An Introduction to the Perennial Philosophy, edited by Martin Lings and Clinton Minnaar. Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, 2007.

|

|

|

|

|

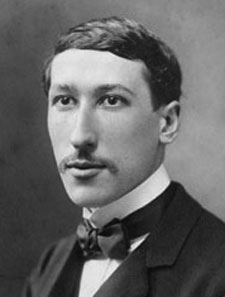

the young René Guénon |

|

René Guénon around 1925 |

| |

|

|

|

René Guénon in Egypt |

|

The Guénons in Egypt |

| |

|

René Guénon at his work desk in Egypt |

|

|

|

The single best source for books in English by René Guénon is sophiaperennis.com. Click on the following link to see a list of Guénon's books in English, along with detailed summaries, publication information, and links for ordering.

|

|

|

|

|

|